-

Home / Leadership Theory - Empathy and the Benefits of Failures, Crises, and Traumas

Was this valuable to you?

other links and editorials from c_prompt

I was speaking with someone the other day (let's call her Jane), learning more about her life experiences. When getting to know potential friends, I have minimal interest in their family, friends, education, career, or financial wherewithal, except as a means to a deeper understanding of who they choose to be. What interests me more are the choices they've made and, more importantly, why these choices were made over alternatives.

Why? Because chance drives so much in our lives. To me, a person's ability to reason is the most important part of character. How we reason drives what we choose. Granted, responding to chance, the choices we make don't always yield the results planned. In fact, sometimes we make choices based on principle alone, knowing full-well they won't turn out well. For example, political activists can be so passionate about a principle that, with certainty of imprisonment, they protest against tyrannical government (or do I repeat myself?). So my logic is this: if character is primarily the result of choice - not chance - scrutinizing someone's choices in the context of their experiences will lead me to better relationships (not to mention help avoid negative and harmful people).

It's not clear why this popped into my mind but, as our conversation continued, I realized there was an overlap between what I look for in friendships and the characteristics of leaders. Could it be that I was subconsciously looking to befriend leaders?

The good life

Some people are born lucky, with health, supportive parents, financial comfort, good educational access, and the like. Others are born with life-altering ailments, or into broken homes, financial distress, and school environments that do more harm than good. When it comes to leadership, life experiences are highly relevant to effectiveness. Surprisingly, it might be that the more failures, crises, and traumas you've experienced, the more potential you have for leadership and the greater an impact you can make. To me, this wasn't intuitive, but it seems reasonable now that I've worked through the theory (which I'll get to in a moment).

Take Jane, for example. I'd describe her as, overall, happy with her life. From all indications, she grew up in a supportive and positive environment. She's intelligent, independent, attractive, healthy, financially secure, genuine, friendly, low-key, truthful, and has positive goals. Although she studies and earns top grades, she explains she doesn't like to think too much, especially about problems that don't affect her life. "Why do I need to know why?" she quips.

She's at peace with herself (which likely also has something to do with her Buddhist beliefs), wouldn't compare herself to others, doesn't seem to consider it her business what others think (of her or any other topic), and doesn't sweat the small stuff. In fact, although I can't claim to know Jane that well, she doesn't even appear to sweat the large stuff. From what I'd uncovered, she's really only had three overly "significant" events in her life: divorce, the (expected) death of her father, and moving from a high-paying, travel-heavy, stressful job to graduate school for a completely different field in a small town of a different country. She described her choices and her life's events somewhat matter-of-factly, with very limited (if any) emotion. I get the sense that, if she failed in any of her pursuits, she wouldn't care too much and would just go do something else.

Jane appears to be someone who "goes with the flow," neither interested in disrupting the status quo nor passionate about making a big difference in the world at-large. She doesn't appear to pass judgment on anyone, and I can't fathom her ever being confrontational. (She described how, in her previous job, she didn't want to fire a poor performer because "how would I feel if I was fired?" Her boss forced the issue and she eventually succumbed, spending "many hours explaining to [the poor performer] why it wasn't working out.") She smiles and laughs often. I believe most would welcome her friendship.

Speaking with Jane, you don't get the sense she's experienced much pain in her life or, if she has, the calm (and calming) nature of her personality hasn't let the pain interfere with her contented outlook. Perhaps the only thing she lacks is romantic love - she'd like to find it again. But, even with this loneliness, you get the sense she'll be happy and lead a fulfilling life.

And that got me thinking: given all her fine qualities but an absence of significant, negative experiences, would she be a good leader? According to some leadership theory, it comes down to how well she can empathize.

Great leaders enhance self-esteem

A theory is a set of propositions about how the world works. Its application isn't of much benefit for specific cases. Instead, it helps you determine what is and isn't relevant for further inquiry.

My favorite class in B-school was a leadership theory course. Leadership is an important subject because it helps motivate and mobilize others to commit to our own values (cf. managers, which are systems of control). We learned about many characteristics of great leaders and how psychology plays such an important role. I left the course understanding a plethora of leadership perspectives and attributes (some more commonsensical - like courage and generating initiatives to mobilize people - than others, such as making decisions with which no one agrees and memorializing mistakes to institutionalize memories, discourage repetition, and pass-on lessons learned). I also learned that, no matter the combination of attributes, effectiveness was very much dependent on context.

The foundational premise of the course was that all great leaders are empathic: the ability to understand how people are thinking and feeling by putting yourself in their shoes. These leaders understand that self-esteem is critical to their followers and try to identify with the objects of their followers' self-esteems (e.g., values, behaviors, people). As those objects do well, self-esteem is enhanced. Likewise, when the objects are performing poorly, self-esteem is diminished (and can even lead to rage if the object is devastated). Great leaders are highly introspective and understand which of those objects they control or influence in order to contribute to their followers' self-esteems.

In other words, great leaders elevate their followers by nourishing what's important to them, thus enhancing their self-esteems.

How do leaders help build self-esteem in others? One method is to provide opportunities to potential followers that are directly tied to the objects of their followers' self-esteems, publically idealize those objects, and then openly fight for the objects. Such courage and admiration by the leader provides followers a source of strength. Being charismatic in delivery certainly helps enhance the breadth and depth of a leader's reach, but charisma isn't itself a requirement.

Being public with their support also provides an impression to followers: "here is a role model to emulate; I want to be like him." Oftentimes, the impression leaders leave can be just as important, if not more important, than what or how they communicate, the disruptive conditions they create for change, or the techniques they use to manifest new expectations. Part of the reason leaders are such great motivators is because followers believe in them (and, sometimes, vice versa). The impressions they leave even help transform followers into leaders themselves and institutionalize behaviors.

Great leaders connect via empathy

But to impress and motivate followers enough to believe in you and follow your ideas, there has to be a connection. This was a particularly insightful learning for me: being able to empathize greatly increases your chances to connect. This is the tie to life experiences. Great leaders understand the benefits of failures, crises, and traumas, and are able to draw upon the knowledge gained from their own negative experiences. From such understanding and knowledge, leaders are better able to sense, perceive, and recognize the applicable emotions and objects in others and, thus, are better equipped to leverage and frame those emotions and objects.

You see, leadership all comes down to psychology. When people fail, their self-esteem is reduced. Trying to increase their self-esteem, they lower their barriers to change and are more willing to try new approaches in order to succeed. Additionally, it can also generate a lot of energy on their part as they try to get their self-esteem back up. Similarly, crises encourage you to abandon the status quo, be creative and innovate, work hard, commit, and move in new directions. Trauma trains you to deal with enormous emotional and physical stress.

Leaders harness these experiences in followers, and are much more effective in forming a connection if they've "been there, done that." As you probably know from your own experiences, the emotions from these negative events become integrated with (imprinted into?) your psyche, providing constant reminders of warning signs and dangers, compelling you into an alert state of being, and offering strategies to deal with similar situations (i.e., what worked before, and what didn't). The associated emotional states are convenient to access and immediately triggered at the first recognition of trouble. Taken together, these negative experiences provide a sense of protectiveness, connection, compassion, and a guide for a way out. They also allow you to quickly gain perspective into another and apply the appropriate criteria for judgment. If a leader can trigger any of that, he's created an instant connection with you.

It makes sense, right? When you've experienced the feelings resulting from these negative events, it's much easier to be aware, understand, and appreciate what others are going through. You and the other are both no longer self-focused and alone in distress. If you're a leader, recalling those feelings puts you in a somewhat vulnerable state as you remember what it was like. That provides a shared connection. From that connection, you guide and build.

As luck would have it, context matters

Sure, there are probably plenty of effective leaders who aren't empathic or don't have significant negative experiences to draw upon. A great leader needs to have the right skills and attributes, but those will vary depending upon context. We shouldn't discount that "being in the right place at the right time" is a highly critical factor relevant to success. Applying an Aristotelian hyperbaton, leadership skills (alone) do not a leader make.

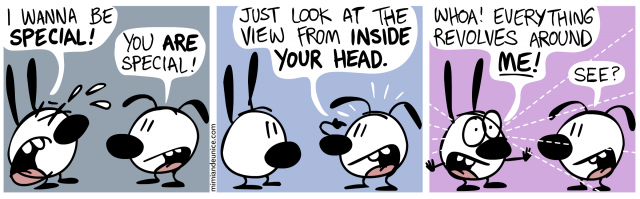

For example, some leaders can be described as narcissistic. Yet, I'm sure you can easily see how a tendency for narcissism could have negative implications and quite the opposite effect desired in some situations. Narcissism might work in industries like banking, but would Mahatma Gandhi or the Dalai Lama be considered great leaders if they were narcissistic? Unlikely. Similarly, you can't expect the skills on a basketball court that lead a team to victory to be as effective when leading civil disobedience against government tyranny or leading innovation of new technologies.

So we must be careful when considering and evaluating empirical evidence that determine which leadership skills to teach and emulate. Searching for leadership, you find well over 100,000 books on Amazon alone. That's quite a few opinions and interpretations of leadership examples and guidance. It's also difficult to discern from those references which are truthful, as I would expect many of those books are fictionalized a bit to encourage sales and follow-on speaking engagements.

For example, if we look at the earning statement of a company and find it is highly profitable, can we directly attribute its success to the company's leadership team (or, even more specifically, the CEO or President)? Obviously, the answer must be no. We can't assume there will always be a one-to-one relationship between profitability and leadership. We also can't assume that leadership skills which were historically effective will be likewise in our current state.

Knowledge is power

We, as individuals, try to make sense of the world in a context to which we can relate. To do so effectively requires a diverse set of knowledge so we can more appropriately determine which factors are relevant. I can't tell you exactly the specific attributes that make a great leader. What I believe is that the more I understand how past leaders operated and the more I understand the details of the current context, the more likely I am to recognize the appropriate skills and tools to do an effective job.

Being a good person whom others want to befriend isn't enough to be a leader. It makes sense that your ability to enhance the self-esteems of your followers will make you more effective. I can see how that would make a leader powerful. But knowledge, which comes from experience, is also powerful. Coincidence? I think not.

About business

The best of your business section. From tips for running a business, to pitfalls to avoid, we teach each other the smart moves and help dodge the foolish.